The Rise of a Superpower

Standing Liberty quarters were minted from 1916 to 1930, but the design of these coins relates to issues “in the news” in 2024 and beyond. Indeed, an interesting and not well understood aspect of Standing Liberty Quarters is their reflection of then-recent changes in the foreign policy and military power of the United States. Events from 1898 to 1918 foreshadowed later foreign policy and military actions throughout much of the 20th century and in the present.

From the 1890s until President Wilson’s decision in 1917 to ask Congress to declare war on Germany, the whole approach of the United States toward the world and the role of military policy changed dramatically. The foreign policy and military reach of the United States was no longer limited to the Americas. The U.S. had become a world power with a military presence in various parts of the globe. An aggressive foreign policy in combination with an expanded military was used to defend democracy and to fight regimes abroad that engaged in wrongdoing.

Before the 1890s, such a foreign and military policy framework would have been considered unthinkable in the United States. Even in 1916, it was extremely controversial. I am here communicating my interpretations of history, coin designs, the spirit of the nation and events. In politics and history, different analysts “see” the same phenomena in different ways. Of course, some people will disagree with my interpretations of coin designs and U.S. history. I maintain, however, that the conception of the nation in the minds of many U.S. citizens changed from the 1890s to 1917, and that the advancing, armored Miss Liberty and flying eagle on Standing Liberty quarters relate to these changes.

In the design of the Standing Liberty quarter, the United States is symbolized in part by a female representation of the concept of liberty, which relates to traditional American values of freedom and justice. This was not surprising, as a female representation of liberty was part of the design of many U.S. coin types from 1793 to the early 1900s. Importantly, the female personifications of liberty on the Standing Liberty quarter (1916-30), the Saint Gaudens $20 gold coin (1907-33) and the Walking Liberty half dollar (1916-47) are stronger, more vigorous and forward-moving than the female figures in the designs of U.S. coins in the 19th century.

On the Standing Liberty quarter, Miss Liberty is stepping energetically in the direction of the person viewing the respective coin. The flying eagle on the reverse and the adding of armor to Miss Liberty in 1917 are especially relevant. Moreover, the female personification of liberty on this quarter is bold and muscular. She does not have the delicate body of a fashion model.

Unlike in many works of art in the U.S. during the 19th century, the female liberty on the quarter is not a representation of knowledge, ethics or agriculture. Furthermore, on the quarter, she is not a flying goddess as Miss Liberty or a female representation of the United States was often depicted on medals, on paper money and in paintings during the 19th century.The concept of liberty on the Standing Liberty quarter was designed to show strength. She is leaving an area behind solid walls, the already-protected boundaries of the United States, and is moving forward into the rest of the world.

Her outstretched strong arm holds a modest olive branch, which indicates that the U.S. is willing to negotiate a peace treaty, yet is powerful enough to win wars. Her large shield has the emblem of the U.S. shield in the middle of it, thus a double-shield, literally and philosophically. She is prepared to defend liberty in principle. Miss Liberty on the Standing Liberty quarter is announcing that the U.S. is ready to fight to protect liberty at home and abroad.

There are multiple differences between Type One (1916-17) and Type Two (1917-30) Standing Liberty quarters. The most noticeable difference is that one of Miss Liberty’s breasts is exposed on Type One coins.

From the 1970s until the 1990s, it was sometimes incorrectly stated in coin collector publications that the Type Two Standing Liberty quarter came about because there was a loud public outcry over the exposed breast of Miss Liberty on Type One Standing Liberty quarters. As far as I know, evidence of a public outcry has never been found.

In the early 1900s, it was common for sculptures and other forms of art, which were often displayed in public places, to feature nudity. Hermon MacNeil was the designer of the Standing Liberty quarter and some of his earlier sculptures are prime examples of the acceptance of nudity in sculptures in the United States during the early 20th century. Some sculptures by A. Alexander Weinman, the designer of the Walking Liberty half dollar, also feature naked body parts that would not have been shown in mainstream sculptures during the second half of the 20th century.

I suggest that the justifications in 1917 for the change in design were part of a smokescreen to deflect attention from a controversial military-related change in the design. There were no very public, influential complaints about any aspect of Type One Standing Liberty quarters.

The legislation that passed Congress in July 1917 allowed for just minor changes in the design of Standing Liberty quarters. There was no mention of Miss Liberty’s chest or any other part of her in the law that authorized changes in the design.

Legendary researcher Don Taxay suggests that Type Two Standing Liberty quarters (1917-30) were “illegal” issues as the law passed during the summer of 1917 did not allow for a change in the design of Miss Liberty. See Don Taxay’s U.S. Mint And Coinage (NY: Arco, 1966). I conclude that Taxay was interpreting the coinage laws too narrowly and not properly interpreting the broad political picture in 1917.

This law did explicitly allow for the changes made to the design elements on the reverse (back of the coin). On Type Two Standing Liberty quarters, the eagle was moved closer to the center of the reverse. Three of the stars that were at the sides of the eagle on Type One Standing Liberty quarters (1916-17) were moved below the eagle on Type Two coins (1917-30).

The most important difference, which was not authorized or even mentioned in a law, between Type One (1916-17) and Type Two (1917 to 1930) Standing Liberty quarters was the adding of armor to Miss Liberty’s chest, though not because the adding of armor covered a naked breast. If the primary objective was to cover a naked breast, then the change in design would have been handled differently, probably in an elegant manner.

It would have been easy to cover both her breasts in the design with a representation of a piece of women’s clothing, either something that was consistent with pictures of goddesses in American art or an article of clothing that was considered fashionable in 1917.

During the late 19th century, female concepts of liberty, justice, agriculture, education or of the nation as a whole were very common in American art and are found on quite a few paper money issues. In terms of design, there were many possible ways in 1917 to cover the breasts of Miss Liberty on the quarter in a noncontroversial and artistically impressive manner.

Artistic merit and historical accuracy were not considerations, as both her breasts are covered with medieval armor, which was not artistically appropriate and was certainly inconsistent with fashions in 1917! This medieval armor covers both breasts and a sizable portion of her upper body.

This armor on Type Two Standing Liberty quarters (1917-30) relates to the true theme of the design in my opinion: U.S. military power and the emergence of an aggressive foreign policy. As the idea of the U.S. fighting in World War I was splitting the nation, the reasons for adding armor to Miss Liberty were not mentioned in the law that passed in July 1917.

Quarters are used every day by U.S. citizens with a wide range of political views. U.S. Congressmen did not wish to hurt the feelings of U.S. citizens who were opposed to the foreign and military policy that came to be in the late 1890s and led to the U.S. declaring war on Germany in 1917.

On the Standing Liberty quarter, the position of her head is important too. Traditionally, in heraldry, a human figure facing to her left, which would be an observer’s right, is looking towards the east. Europe is to the east of North America. Miss Liberty on the quarter in 1916 indicated that the U.S. was very concerned about the war in Europe and was prepared to become involved for reasons relating to liberty, but not to further imperialist aims.

The large eagle on the reverse of the quarter is already flying, meaning that the U.S. was already a military power in 1916. On most designs of silver and gold U.S. coins in the 19th century, the eagle is not flying. On many coins, the eagle is standing and inactive, or is depicted as a symbol rather than as a living creature.

An exception was the flying eagle on the reverse (back) of silver dollars dating from 1836 to 1839. This was symbolic of a young nation becoming an adult nation, with her own foreign and military policy. By 1836, the U.S. had consolidated much territory in North America, had exerted some influence in Latin America and was thought to be ready to “fly” on her own.

Unlike on many coins throughout the history of civilization, there are no swords in the design of the Standing Liberty quarter. Unlike on many other U.S. coins, there are no military arrows in the design of the SLQ. The absence of swords and arrows on a circulating coin introduced in 1916 indicates that the U.S. was interested in protecting democracy and liberty, not conquering.

In recent times, President Putin of Russia has cemented his power with more control of Russian citizens, including a policy of government monitoring of all Internet access from within Russia. The invasion of the Ukraine by Russia in 2022 prompted the U.S., Great Britain, France and Germany, among other allies, to provide extensive military support to the Ukraine. Is this relevant to the U.S., Great Britain and France being on the same side in World War I to fight the imperialist advances of the regime of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany?

It is also true that since Xi Jinping became the leader of China in 2013 his power has increased, and he now sometimes appears as an emperor rather than as a president. The government in Beijing has claimed and has been seeking to aggressively acquire islands from Vietnam, Thailand and Japan.

On Nov. 15, 2023, President Joe Biden referred to Xi Jinping as a “dictator” in a press conference. Earlier, on Sept. 18, 2022, Biden became the first U.S. President in generations to explicitly say that U.S. military forces would defend Taiwan in the event of an invasion by China. Later, it was revealed that U.S. special forces were stationed in Kinmen (Quemoy), the part of Taiwan that is physically closest to China. Kinmen is more than 200 miles from Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, yet just a few miles from Xiamen, a city in China. A point here is that there is a connection between the symbolism in the design of the Standing Liberty quarter and U.S. policies in the present.

From the 1890s to 1919, concerns about Japanese influence in Hawaii, alleged aggression by Spain relating to Cuba, and expansionist aims by Germany all contributed to changes in U.S foreign and military policies. The reflections of changes in policy in coin designs occurred at various times and were often subtle. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt asked Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the leading sculptor in the nation, to design the medal for his inauguration in March 1905. Later, Roosevelt made it clear that he wished for Saint-Gaudens to prepare new designs for America’s coinage in general, starting with gold denominations. Roosevelt and Saint-Gaudens were personal friends.

Earlier, Theodore Roosevelt was “sworn in” on September 14, 1901, shortly after President William McKinley was assassinated at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Hermon A. MacNeil, later the designer of the Standing Liberty quarter, won a major award for a sculpture that was exhibited at this exposition in 1901 and MacNeil was the designer of the official award medal of this exposition, which remains popular with collectors. Was MacNeil the designer of the medal that he was awarded as a winning sculptor at this expo?

The Pan-American Exposition is a circumstantial “connection” between Hermon MacNeil and President William McKinley. MacNeil’s art was well known to those involved with this exposition and to visitors. It is likely that McKinley was aware of MacNeil’s art and that MacNeil was aware of McKinley’s foreign policy, as media coverage regarding the Spanish-American war was overwhelming. After McKinley was assassinated and Vice President Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, it was clear that Roosevelt favored a foreign and military policy that was much different from U.S. policies before the 1890s.

The Panama Canal

The Panama Canal Zone was created in November 1903 while Theodore Roosevelt was president. A section of Panama became a United States territory. The U.S. government bought land from private and local government sources. The Panama Canal was built, paid for and owned by the United States. For more than sixty years, the Canal Zone was controlled by the United States, with a significant U.S. military presence. Before the 1890s, such a situation would have been unthinkable in the annals of the U.S. government.

In addition to contributing greatly to international trade, the Panama Canal served a military purpose. The U.S. was in control of the most efficient and only very practical route of traveling by boat from the Atlantic ocean to the Pacific ocean. Before the Panama Canal was constructed, ships had to take the time to go around Chile and Argentina.

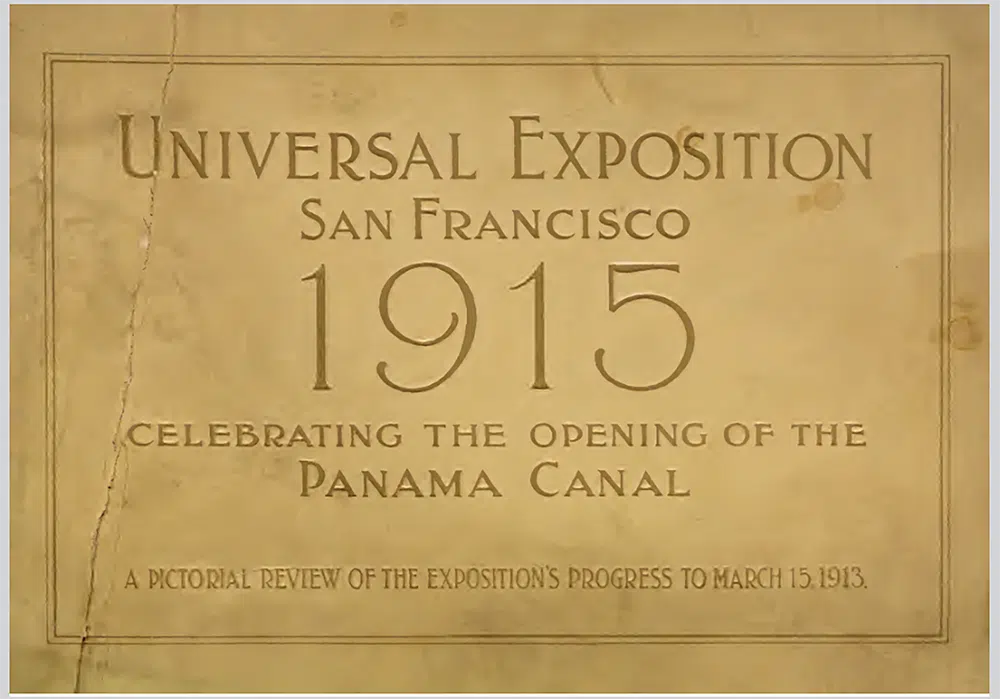

The Panama Canal opened in 1914 and was honored in 1915 by the holding of the Panama-Pacific Exposition in California. This canal and this exposition are relevant to changes in military policy and to the designs of Standing Liberty quarters.

A rejected version of Hermon MacNeil’s obverse (head side) for the Standing Liberty quarter featured two dolphins, one on the left and the other at the right side of Miss Liberty. It is not a coincidence that two similar dolphins appear in the reverse design of Pan-Pac commemorative 1915 One Dollar Gold pieces. There are also dolphins depicted on octagonal Pan-Pac $50 commemorative gold coins. In 1915 and 1916, dolphins opposite each other symbolized the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and the function of the U.S. owned Panama Canal to connect them.

The Emergence of A Superpower

During the early years of the United States, naval power was generally only used to defend U.S. ships abroad and to protect trade routes. It was also used in the ‘War of 1812’ to protect the United States against advances by Great Britain. Before trains and later airplanes were invented, ships and shipping routes were of tremendous importance to a nation. In the early 1800s, the military policy of the United States was designed to defend borders and defend international trade by private and government entities in the United States.

The Monroe Doctrine marked a change in policy. President James Monroe is credited with formulating a policy in 1823 that holds that the United States should seek to prevent the expansion of European influence in the Western hemisphere, “the Americas.” Indeed, it was later maintained that Monroe’s point was for the United States to be the superpower in regards to both North America and South America, where the influence of European nations was to be contained, by military force if necessary. From the onset, the Monroe Doctrine was controversial.

The Mexican-American war of 1846 to 1848 related to borders and political situations in North America. Earlier conflicts within North America are beside the point of the U.S. becoming a world power during the period from 1898 to 1918.

During the 1850s and 1860s, the U.S. was embroiled in conflicts within the nation and their aftermath. During the 1870s and 1880s, U.S. citizens were very concerned about economic growth and there was little interest in military missions.

President William McKinley (1897-1901) was pushed by political allies, circumstances and many voters to unenthusiastically implement a policy that was consistent with the Monroe Doctrine and went beyond that doctrine. McKinley, however, was consistently a believer in the need for the United States to take over Hawaii, then an independent nation. The government of Japan seriously considered intervening in internal political conflicts in Hawaii during the 1880s and 1890s.

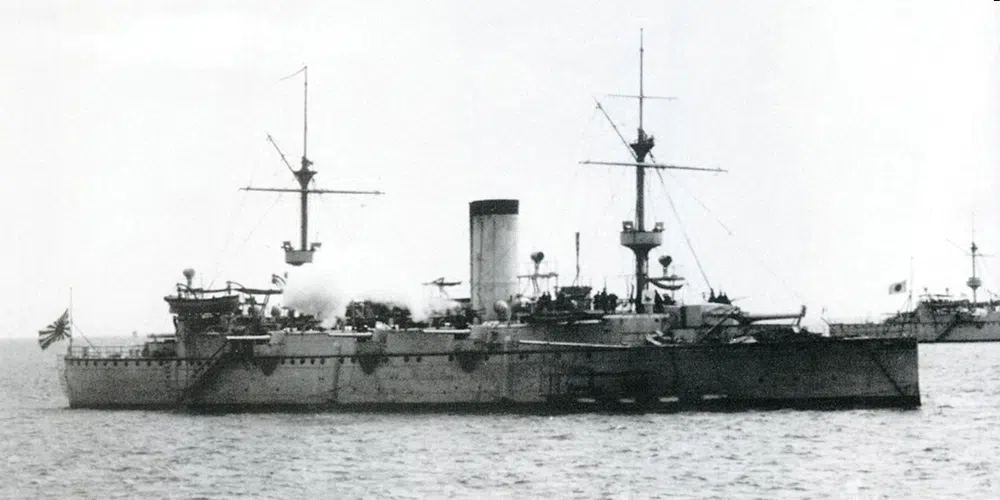

In the mid 1890s, at least two Japanese warships visited Hawaii. The Kongo was present when the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown in 1893, though Japan was probably not involved in that change of government. The Kongo departed Hawaii not long after an advanced Japanese warship, the Naniwa arrived. By May 1893, both the Kongo and the Naniwa were back in Japan, but the Naniwa traveled to Hawaii again in December 1893 and did not return again to Japan until April 1894, according to public sources. U.S. officials were definitely very concerned about Japanese influence in Hawaii.

Even before the Spanish-American war began, President McKinley sought Congressional approval fora takeover. In 1898, Hawaii became a territory of the United States with

a substantial U.S. military presence, especially at Pearl Harbor.

The conflicts in Hawaii were mild in comparison to the conflicts in Cuba. During the second half of the 19th century, Cuba, which remained a colony of Spain, was divided among those who were loyal to Spain and those who demanded that Cuba become an independent nation. Indisputably, the Spanish Empire was one of the largest and wealthiest of all time. From the early 1500s to the early 1800s, Spain controlled a significant portion of the world’s land mass, while mining massive quantities of silver and gold. For centuries, Spain, France and Britain were leading superpowers.

Early in the 19th century, the invasion by France and allies of the Iberian peninsula, which includes Spain and Portugal, led to the fall of the Spanish Empire, though the decline occurred over a period of decades. In the early 1890s, Spain still had Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, among other possessions. Spain thus had a large presence near the United States and in the Far East.

Civil wars in Cuba “broke out” during three different time spans during the 19th century. While the United States was officially neutral until 1898 and sometimes prevented Cuban revolutionary forces from mounting invasions into Cuba, the U.S. government allowed revolutionary forces to organize, raise funds and be based in Florida. U.S. forces, however, tended to hamper the efforts of revolutionary forces to bring weapons into Cuba to fight the Spanish-Colonial government. The U.S. thus allowed bases for Cuban revolutionary forces, but would not let them win. All this changed in 1898.

Although several factors contributed to a change in U.S. policy toward Cuba, a major event was the explosion that devastated the USS Maine, an American warship, in Havana Harbor on Feb. 15, 1898. More than 200 U.S. military personnel were killed.

The USS Maine was in the harbor to protect U.S. citizens and American business while revolutionary and Spanish-Cuban colonial government forces were in conflict. The cause of the explosion that sank the USS Maine was never formally documented. At the time, it was generally believed that the Spanish-Cuban colonial government, perhaps Spain herself, was at fault, though there was not a consensus among U.S. officials regarding the cause. Even now, no one really knows.

Although many historians suggest that the explosion may have been accidental, I doubt that this warship blew up by accident. It was extremely advanced, expensive and well maintained. Clearly, the Spanish-Cuban colonial government had a motive to sabotage the USS Maine. If so, the Spanish-Cuban colonial government probably figured that the American people would not support U.S. forces fighting in Cuba, and the U.S. would just withdraw. For most of the 19th century, U.S. foreign and military policy had been largely isolationist rather than interventionist.

The USS Maine and her sister warship, The USS Texas, were both ordered in 1886. The U.S. government was concerned about advanced naval warships and weaponry being deployed by multiple nations in South America. The USS Maine went into service in the late 1880s and the USS Texas was launched in the early 1890s. They were both large and very sophisticated for the time period. Others, not just the Spanish-Cuban colonial government, may have had a motive to destroy the USS Maine.

After the USS Maine blew up, President McKinley was reluctantly persuaded to take a more aggressive position. The U.S. government negotiated with the government of Spain in regard to the fate of Cuba. An agreement was not reached. On April 20, 1898, the U.S. Congress ended the official policy of neutrality and authorized the use of force to secure the independence of Cuba from Spain. Soon afterward, the U.S. and Spain declared war on each other.

Perhaps surprisingly to many world leaders, the U.S. easily won the war with Spain. A treaty later in 1898 gave the U.S. temporary control of Cuba. Moreover, the U.S. received clear, long-term title to Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines, though Spain had to be paid millions of dollars for infrastructure left behind. In less than one year through the Spanish-American War, the U.S. amassed a small holding of colonies, including noteworthy bases in Asia.

Guam was later to become a major location in World War II. U.S. naval bases in Cuba and Puerto Rico became very important in later eras. Although people in 1898 or in 1916 could have not have known the entirety of the long-term consequences of the Spanish-American War, it was clear by 1916 that the balance of power in the world had changed as the U.S. became very powerful. In 1899, Spain sold other colonial possessions to Germany, and was never again a world power.

Although the period from 1899 to 1915 was relatively peaceful for the United States, it was apparent that the U.S. had far more power than the U.S. had before the 1890s. The idea of expanding U.S. influence became a part of the culture of the nation, and was a hotly debated topic. As World War I began in 1914, it could not be ignored. Former President Roosevelt strongly argued that the U.S. should become involved.

The $20 gold coin (Double Eagle) designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens at the request of President Roosevelt, made its debut in 1907. Miss Liberty on the obverse of the Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle (U.S. $20 gold coin) was patterned after, or at least very much influenced, by a famous statue of Niké of Samothrace, the Ancient Greek personification of victory. That statue dates from around 190 B.C.

Unmistakably, Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ monument commemorating Gen. William Sherman features Saint-Gaudens’ version of Niké of Samothrace, a symbol of victory, leading Gen. Sherman. Both the Miss Liberty on the Saint-Gaudens Double Eagle and the Miss Liberty on the Standing Liberty quarter are strong female personifications who are clearly moving forward rather than being still as on many U.S. coin designs of the 19th century.

On early sketches by Saint-Gaudens of ideas for $20 gold coins, Miss Liberty had wings like those on ‘victory’ in the Sherman monument and on the famous Niké of Samothrace statue. The Sherman monument was unveiled in New York City’s Central Park in 1903. It is logical to figure connections between military victory, President Roosevelt’s “speak softly and carry a big stick” foreign policy, Roosevelt’s selection of Saint-Gaudens to design coins, Saint-Gaudens Double Eagles and Standing Liberty quarters.

Roosevelt was Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1898 and he was very enthusiastic about the Spanish-American War. He resigned his civilian post and became a Lieutenant Colonel in a volunteer regiment, which fought in Cuba.

Although the U.S. had yet to become involved in World War I, it was very much in the news during a period in 1915-16 in which new designs for U.S. silver coins were considered. Though no longer holding a political office, Roosevelt exerted influence.

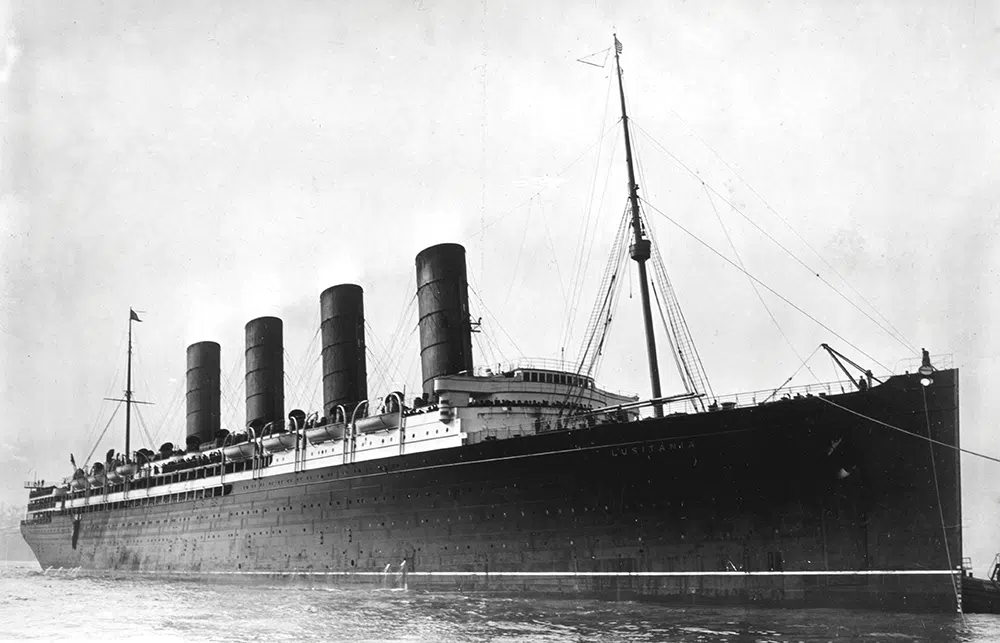

In May 1915, a German submarine sank The Lusitania, a British passenger ship. More than 1,000 people perished, including more than 100 U.S. citizens.

While some revisionist historians have argued that The Lusitania probably was carrying weapons in crates or boxes, it is clear that The Lusitania was civilian in nature and was unable to defend herself. President Woodrow Wilson issued a formal protest, though he did not then favor military action.

In March 1916, a German U-boat torpedoed a French passenger ship, Sussex, killing dozens of people and seriously injuring several U.S. citizens. Afterward, the U.S. government threatened to cut diplomatic ties with Germany. Hermon MacNeil, the designer of the Standing Liberty quarter, must have been aware that German submarines were sinking passenger ships, some of which had U.S. citizens on board.

It is boldly stated in the annual report of the Director of the United States Mint, on July 15, 1916, that the “design of the 25-cent piece is intended to typify in a measure the awakening interest of the country to its own protection” (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1916, p. 7). The term “awakening” here refers to a process that was affected by foreign events. Moreover, control of the Panama Canal, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines were not needed for the nation’s “own protection,” as that term was understood in the 19th century. By 1916, the term “protection’” as it relates to the nation really referred to “the awakening” of a will or option to become a superpower.

In February 1917, the German imperial government announced that the German Navy would again, without advance notice, attack unarmed passenger ships near the coasts of Europe. This prompted President Wilson to terminate formal relations with Germany.

U.S. policy was affected by the interception in early 1917 by the British of the Zimmerman “cable” from Germany to Mexico, a secret message regarding a German offer to assist Mexico if the U.S. declares war on Germany. Arthur Zimmerman was one of the highest-ranking officials in the German government.

Basically, the German government informed the Mexican government that, if the U.S. entered World War I, the German government would be willing to militarily assist the Mexican government in regaining territory that had been lost to the U.S. in earlier conflicts, including Texas and Arizona. Understandably, many U.S. citizens were outraged by the realistic possibility of a joint Mexican-German invasion of Texas and Arizona.

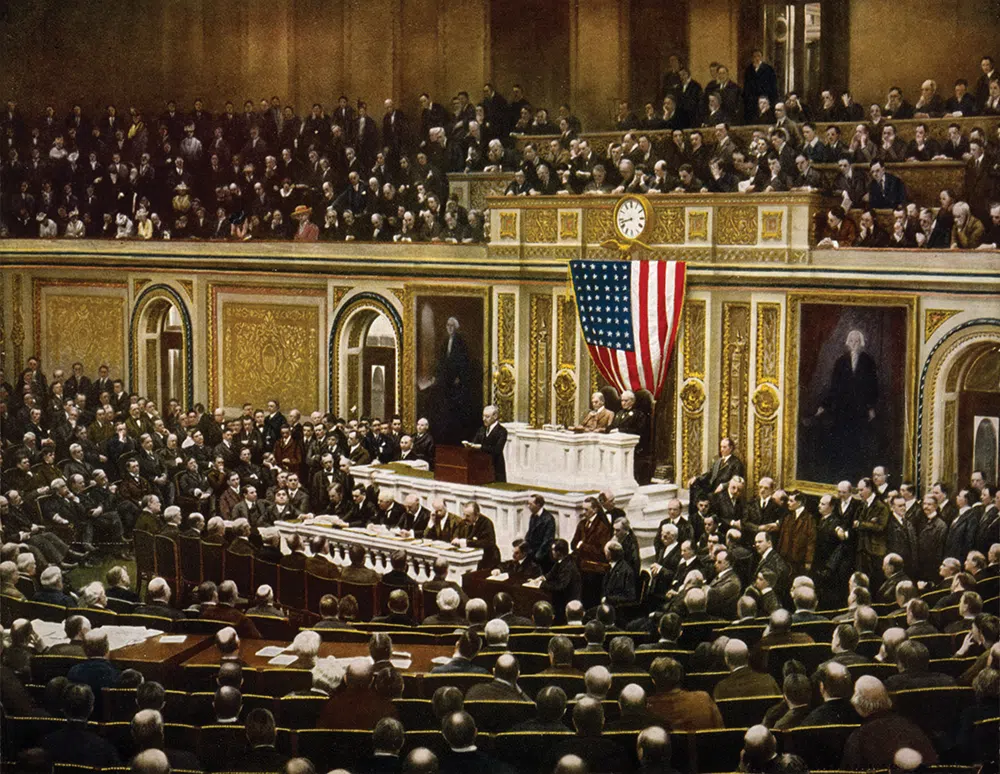

Undoubtedly, there were multiple reasons that contributed to President Wilson changing his mind in April 1917 and asking Congress to declare war on Germany. The House of Representatives voted 373 to 50 in favor of the U.S. entering World War I and the vote in the Senate was 82 to 6. Opinions in the U.S. about foreign and military policy had changed much from 1898 to 1917.

The U.S. became involved in a war involving superpowers. This new role for the U.S. is reflected in the design of the Standing Liberty quarter. Miss Liberty is looking toward Europe as she is confidently marching forward away from the walls that protected her within the borders of North America and toward a more dangerous realm. She carries a large shield and wears armor on her chest to protect her from the enemies yet to be encountered. She is embodying liberty and freedom, yet she is showing her willingness to negotiate, from a position of strength, with an olive branch, which signifies peace.

Greg Reynolds is an independent rare coin consultant who has written more than 780 articles, which have appeared in nine different coin publications, and many private reports for clients. Greg has carefully examined a substantial percentage of choice and rare U.S. coins in existence and a large number of condition rarities, plus thousands of vintage British, Western European and Latin American coins. Email: Insightful10@gmail.com

Images of coins and patterns are shown courtesy of Stack’s Bowers Galleries of Costa Mesa, California (www.stacksbowers.com). Historical images are in the public domain in the United States.