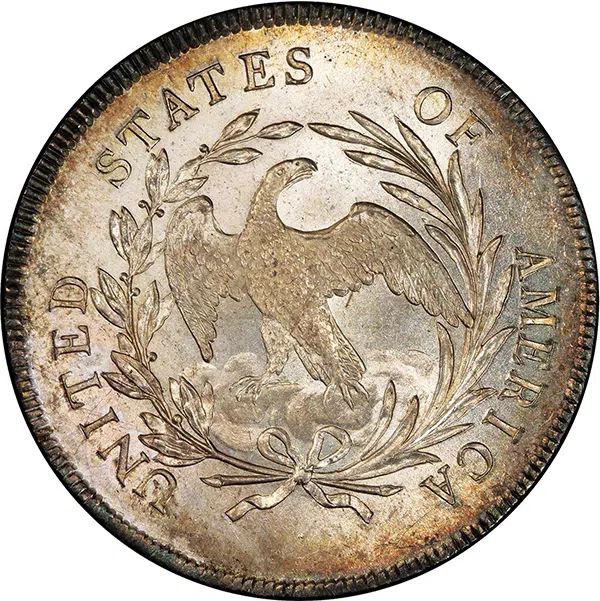

Official U.S. silver coins were first minted in 1794, and the new coinage system of the United States revolved around the silver dollar, as this was the base unit. The U.S. silver dollar, in turn, was based upon the Spanish milled dollar (8 reales coin).

Before the 20th century, the main unit of money in a society was generally defined by a physical amount of gold or silver. Throughout history, however, an amount of gold or silver that was determined by a government to define a unit of money was subject to change for political or economic reasons.

To understand the U.S. dollar in the present, it may be necessary to have some understanding of how it came about. To think about the history of the dollar and U.S. coinage in the past, it helps to refer to grains.

For centuries, grains were used as a measure of weight for many things, including gold and silver. 480 grains equals one troy ounce and 5.500 grains equals one troy pound. 7.000 grains equals one standard or regular pound. Original amounts in grains tend to be clearer and more straightforward then their equivalents in troy ounces, which are usually awkward approximations.

Amounts in grains can easily be understood in troy ounces if it is remembered that 480 grains equals one troy ounce, but a conversion from an historically noteworthy number of grains to troy ounce may include many digits to the right of a decimal point. For example, before the Coinage Act of 1853, a dime was mandated to have 37.125 grains of silver, a number that seems sensible and can be remembered. The conversion, however, works out to 0.07734375 troy ounce, a number that is awkward and difficult to remember. Ten times this number, 0.7734375 troy ounce, is the amount of silver in a U.S. silver dollar, which is better remembered as 371.25 grains.

In the past and present, troy weights usually refer to gold or silver and their connection to money. Before the 20th century, the U.S. dollar was legally defined as a weight in silver and gold, but changing market conditions often made it difficult for the legal definitions to be practical or even valid in reality.

After 1851, the relationship between the face values of U.S. silver coins and their silver content became complicated. Before 1851, the value of the silver in every U.S. silver coin was equal to its face value in dollars or cents: A quarter had a quarter’s worth of silver. A dime had a dime’s worth of silver.

Many were shocked in 1851 when a Three Cent Silver coin was introduced that had only 2.5 cents worth of silver. Merchants, though, accepted them at face value.

Although the American colonies became a nation upon the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the U.S. government did not operate a mint until 1793.”

Before 1851, it was certain that a U.S. dollar referred to 371.25 grains of silver (about 0.7734 troy ounce) and a half-dollar coin had half as much silver. All U.S. silver coins were alloyed with copper. I am here referring to the net amount of silver, not the total weight of the coins.

By 1853, all newly made U.S. silver coins, except silver dollars, did not have enough silver in them to meet the official government valuation in silver of their respective face values. For example, before 1853, a dime had 37.125 grains of silver: one-tenth of the amount of silver in a U.S. silver dollar. Afterward, each dime had 34.56 grains of silver, a reduction of about 7%.

Remarkably, in 1935, the last U.S. silver dollars minted to be spent at face value (one dollar) still had exactly 371.25 grains of silver (0.7734 troy ounce), the same amount of silver that U.S. silver dollars were required by law to have since 1794.

During most of the history of the nation, the U.S. government officially connected silver to gold to U.S. dollars by law (bimetallism). The Coinage Act of 1792 required that 15 ounces of silver equal one ounce of gold, so the gold in a U.S. $5 gold coin (half eagle) weighed one-15th of the total weight of all the silver in five silver dollars.

From 1795 to 1833, each $5 gold coin contained 123.75 grains (0.2578125 troy ounce) of gold. As each silver dollar had 371.25 grains of silver, the total amount of silver in five silver dollars was 1856.25 grains (3.867188 troy ounces), precisely 15 times the weight of the gold in a pre-1834 U.S. $5 coin.

Before 1851, the value of the silver in every U.S. silver coin was equal to its face value in dollars or cents: A quarter had a quarter’s worth of silver. A dime had a dime’s worth of silver.”

In 1834, the official U.S. silver to gold ratio was changed to 16:1 because the market price of gold bullion went up. A century later, in 1934, the official ratio was changed again by the U.S. government, though the nation had really been on a gold standard, rather than a dual silver and gold standard, since the passage of the Coinage Act of 1873.

The values of silver and gold in U.S. dollars became complicated during the 1960s. Before 1964, the U.S. government issued paper money known as “silver certificates” and people spent them every day. In the early 1960s, production of silver certificates was phased out and entirely replaced by Federal Reserve Notes: paper money that was not backed by silver or gold.

In 1968, the U.S. government ended the practice of guaranteeing that U.S. silver certificates could be exchanged on demand for silver bullion. In August 1971, President Richard Nixon announced that the U.S. government was “closing the gold window”; the U.S. government would no longer guarantee a conversion rate between U.S. dollars and gold bullion.

Later developments are beside the point that the U.S. dollar had a legal meaning in silver bullion from 1792 to some point in the 1960s; 371.25 grains of silver per dollar meant that silver was worth about $1.29 per troy ounce. While the U.S. government policy before 1853 was to keep the market price of silver at $1.29 per troy ounce, the policy in the 20th century before 1965 was to keep market price of silver significantly below $1.29 per ounce to discourage people from melting or hoarding U.S. silver coins found in circulation. If the price of silver had climbed significantly above $1.29 per ounce before 1965, it would have been profitable to melt common U.S. dimes, quarters, half dollars and silver dollars.

Why did the U.S. dollar have this meaning in silver? How did the whole process get started? Although the American colonies became a nation upon the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, the U.S. government did not operate a mint until 1793. Under the Coinage Act of 1792, it was against the law for U.S. silver coins to be minted until bonds had been posted by the chief coiner, the treasurer and the assayer, which were important positions. Though U.S. silver dollars did not exist until 1794, the Coinage Act of 1792 defined the U.S. dollar as soon as it was signed into law by President George Washington.

Through market realities and historical development, the Spanish milled dollar (8 reales coin) fathered the U.S. dollar. The Spanish Empire struck 8 reales coins from the 1500s to the 1800s and operated multiple mints. Spanish 8 reales coins, which are Spanish dollars, became the main currency of the world after tremendous amounts of silver were discovered in Spanish colonies in the Americas during the 1500s and 1600s.

The finding of so much silver was not the only reason why the Spanish milled dollar was so widely accepted and became the basis for the U.S. dollar. Why was a Dutch coin from the 1600s or an 8 reales coin of the Spanish Empire called a “dollar’? Dollar is an English word.

Before the 20th century, the U.S. dollar was legally defined as a weight in silver and gold, but changing market conditions often made it difficult for the legal definitions to be practical or even valid in reality.”

Forerunners of the dollar were minted in Tyrol, which spans parts of present-day Italy and Austria. During the 1400s, the government of Tyrol issued large silver coins, which were recognized as a basic unit for commerce and for accounting. These were predecessors of the Joachimsthalers. The Tyrol talers of 1486 are often thought of as the first talers, the large silver coins of Europe that were main units of money in many areas.

The Tyrol talers were known to the people of the village of Jáchymov, which is now in the Czech Republic. According to Wikipedia, this village was founded by Št?pán Schlick in 1516 as Joachimsthal, a German name. A rich silver mine drew a lot of attention.

Soon after the founding of the village, the Shlick family began minting silver coins called “Joachimsthalers.” This name was later shortened to taler and toler. Many German-speaking societies issued talers, which became a standard for silver coins in Europe. There were fractional talers and multiples of talers. Indeed, these were the dollars of Europe.

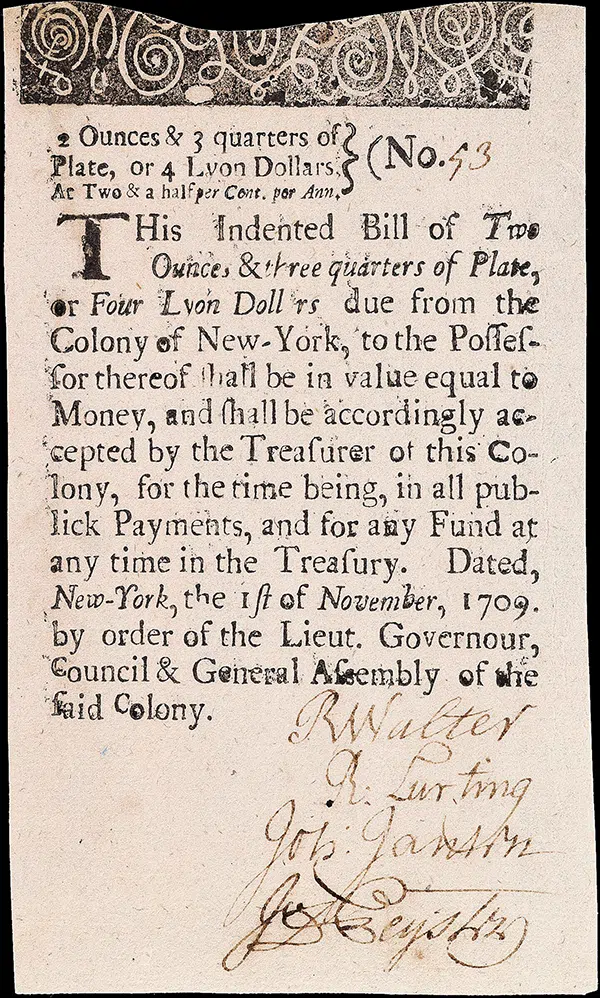

In the late 1500s, the Dutch issued the lion daalder (Leeuwendaalder) for international trade. Six of the seven provinces of the Netherlands issued their own lion daalders, as did individual cities. Lion daalders were intended to compete with German talers.

Dutch coinage was influential. For centuries, the Netherlands featured major business centers. In the early 1600s, the Dutch colonized a region that was later part of the British colony of New York, and the Dutch called this region “New Amsterdam.” Although the English finally took control of New York in 1674, Dutch culture and traditions remained.

The British never minted sufficient quantities of silver coins, given economic activity on the British Isles, coinage needs of British colonies and trade worldwide by British merchants. The British and the Dutch traded with each other to a great extent. The Dutch minted substantial quantities of Lion daalders, so these circulated in British colonies.

Although a lion daalder had only around 320 grains of silver, this amount was two-thirds of a Troy ounce and thus a silver weight that was easily remembered and practical for commerce. Before the talk in the U.S. of a decimal system for coinage, few people in the 1700s would have connected the idea of a decimal system with coinage. The British used multiples of three, four and five for coin values. The Spanish coinage system was based on eighths and multiples of eight. In several European countries, fourths played a role in designing types of coins.

Lion daalders were three-fourths (75%) silver and one-fourth copper, and thus the total weight of a lion daalder, 426.67 grains, was in the same ballpark as the weight of a Spanish 8 reales silver coin and that of most German talers. There were large quantities of lion daalders circulating in North America in the late 1600s and early 1700s. Over time, a Leeuwendaalder was called a lion daalder and then a lion dollar, sometimes spelled with a ‘y’ (Lyon dollar).

“In Maryland, the lion dollar was mentioned as the most important circulating coin in documents of 1701 and 1708,” reports Louis Jordan in an online “book” about American colonial coins on the University of Notre Dame website. In 1709, the colony of New York issued paper money that was explicitly backed by lion dollars. The words “Lyon” and “Dollars” were printed right on this paper currency.

It is thus clear why a Spanish 8 reales coin would be called a “dollar” as it is similar in size and function to German, Austrian, Czech and Dutch coins that were often called “dollars.” Taler, toler and daalder all relate to the word “dollar” in English. In 1768, the third edition of Samuel Johnson’s famous dictionary of the English language implies that the English word dollar is linked to the Dutch word “daler” and refers to either “a Dutch and German coin of different value,” and the British values listed by Johnson would be likely to refer to a Dutch lion dollar and a German taler. In the late 1700s, a prominent dictionary in England, by Thomas Sheridan, defined the English word “dollar” in much the same way.

Spanish milled dollars (8 reales coins) from 1732 on were similar in size and overall weight to German talers and Dutch lion dollars. Spanish milled dollars and fractional denominations, half dollar (4 reales), quarter (2 reales), one real, and half real, were used by Americans to a great extent, before and after the U.S. Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

Spanish milled dollars were standard monetary units of the Americas and the most widely used coins for trade in Asia. As late as the 1870s, while the Spanish Empire was just a shadow of its former self, the Japanese government introduced one-yen silver coins which were near-perfect substitutes for Spanish milled dollars, to be used in international trade.

How did this happen? Why were so many people in different continents frequently using coins of the Spanish Empire, most of whom did not speak one word of Spanish?

In order to understand Spanish milled dollars (8 reales coins) and the meaning of a dollar in the United States before the twentieth century, it is necessary to think about Queen Isabella I of Castile, a large kingdom on the Iberian peninsula, which now features Spain and Portugal.

Aragon and Castile were both large kingdoms that later became part of Spain, though Aragon was not as large or as wealthy as Castile, which included Leon. In 1469, Princess Isabella of Castile married Prince Ferdinand of Aragon.

In 1474, Isabella became a queen in her own right. She was then a Queen Regnant, a ruler, not a Queen Consort, the wife of a king. She inherited the throne of Castile after her half-brother, King Henry, died.

Five years later, in 1479, Prince Ferdinand became King Ferdinand II of Aragon upon the death of his father, John II. The domains of Aragon included Valencia, Majorca, Sardinia, Catalonia and Sicily.

Together, Isabella and Ferdinand ruled a vast region that was effectively Spain, though Castile and Aragon were not legally merged until a much later time. Isabella and Ferdinand were married, but in charge of two separate and extremely powerful kingdoms. If not for their marriage, there may never have been any U.S. silver dollars.

In world history, Queen Isabella is best known as the patron of Christopher Columbus. She granted funds, ships, supplies and a high rank to Columbus. Undoubtedly, many business people, sailors and government officials thought that Columbus was crazy. There were no maps of the Western part of the Atlantic ocean, and no one knew where Columbus would end up. Also, the possibilities of encountering bad storms or hostile military forces must have been considered.

In 1492, Columbus left Castile with three ships. He returned in 1493 with tales of landing on islands that were then unknown to Europeans. He was later to lead three more expeditions to the New World. He is credited with discovering North America and South America. The Spanish colonized many regions in the Americas. Mints were established, so there is a close connection between the journeys of Columbus and the mass production of 8 reales silver coins, Spanish dollars. In 1892-93, Columbus was honored on a U.S. commemorative half dollar at the time of the Columbian Exposition to celebrate the 400th anniversary of his first discovery.

In the 1530s, the first mint in the New World was founded in Mexico City. The mint in Lima did not come to be until 1568. Lima is now part of the nation of Peru.

In 1732, the screw press was used for mass production at the Mexico City Mint. From the early 1500s to the early 1800s, Mexico was part of the Spanish Empire.

In regard to coins dating before 1800, a milled coin was made with a screw press rather than just a hammer and anvil. A screw press is a machine.

According to John Kleeberg in an article in the August 2013 issue of The Colonial Newsletter, Volume 53, Number 2 (NY: ANS), screw presses were operational at the Mexico City Mint in 1732, the Santiago (Chile) Mint in 1751, the Lima Mint in 1752, the Guatemala Mint in 1754, the Bogota Mint in 1759 and the Potosi Mint in 1767. The Spanish Empire had a network of mints in the Americas, all of which produced Spanish milled dollars.

After 1732, Spanish milled dollars were very much preferred to Spanish dollars that were not “milled.” Most of the Spanish silver coins that were minted in Mexico and South America during the 1500s and 1600s were sloppily made. They were often struck on poorly formed lumps of silver. The shapes of hammered 8 reales coins were frequently irregular and were inconsistent over time. Design details were sometimes missing. It was relatively easy to clip or shave the edges of coins that were hammered (struck by hand), inconsistently shaped and weakly struck.

Coins made with a screw press tended to be more precisely round. The unethical removal of silver or gold from well made coins was usually noticeable. Though both were of the 8 reales denomination in the Spanish system, Spanish milled dollars were much better made and had better reputations than the Spanish dollars that were not milled.

Before 1760, Spanish milled dollars became the main units of money in the British colonies in North America. They were preferable to lion dollars and German talers, and far more available than either of those. Indeed, in British Colonial America before 1776 and in the U.S. from 1776 to the 1830s, most people used Spanish Empire coins to buy necessities and luxury items.

Almost everybody in the mid-1700s knew that the Spanish milled dollar was the standard coin of the Americas, yet politicians and businessmen tended not to state this fact in writing. The pre-1776 British colonies and post-1776 U.S. States, however, each had their own monetary definitions. They all used British terms, especially pence and shilling, but the American definitions of these British terms were inconsistent and weird.

In his landmark book, Fractional Money (NY: Wiley, 1930, p. 34), Neil Carothers notes that a “shilling from the British mint was not a shilling in any colony. In Georgia, it was 1 shilling and 3 pence, in Massachusetts 1 and 6, and in New York 2 shillings.”

In his online book on colonial coins on the University of Notre Dame website, Louis Jordan notes that the accounting value of the Spanish milled dollar in various colonies kept changing during the 1700s. At some point before 1776, a Spanish milled dollar was designated to be eight shillings in New York, six shillings in Virginia, six shillings in Massachusetts and seven and a half shillings (7s6d) in Pennsylvania. In London, a Spanish milled dollar was worth 4s6d (four and a half shillings) in true British coins, which were scarce.

A change in perspective became evident on June 22, 1775. The Continental Congress authorized the printing and issuance of a sum of not more than two million “Spanish milled dollars” in Continental Currency (paper money) to fund the Continental Army, the revolutionaries. This order was signed by Charles Thomson, an officer of the Continental Congress, and John Hancock, the president of the Continental Congress. Before the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, the Continental Congress, later sometimes called the Confederation Congress, embodied the government of the United States.

On Sept. 2, 1776, a committee studying gold and silver coins in circulation provided a report to the Continental Congress. Thomas Jefferson was very much involved, though details of the workings of this committee are now unclear.

The primary task of this committee was “to ascertain the value of the several species of gold and silver current in these states, and the proportion they and each of them bear and ought to bear to Spanish milled dollars.” The values of most all types of foreign coins circulating in the U.S. were figured in net grains of silver and in Spanish milled dollars. Certainly, it was clear that Spanish milled dollars were considered the main monetary units, not any British or French coins.

During the 1780s, ideas regarding a system of U.S. coinage were introduced, especially the Morris plan in 1783. For multiple reasons, the U.S. Congress did not then establish a coinage system. Thomas Jefferson and several other influential leaders were in agreement that the Spanish milled dollar should be the basis of any U.S. Coinage system.

There were no U.S. government coins in the 1780s. The contract for Fugio Coppers was not valid and led to fraud. The Articles of Confederation, however, were written in such a way that it was almost impossible for the U.S. government to mint or authorize the production of coins. The Articles of Confederation were replaced by the U.S. Constitution in 1788.

By 1790, there was no longer a debate about the point that the Spanish milled dollar should be the basis for the U.S. monetary system, yet several coinage issues were unresolved. Alexander Hamilton, then Secretary of the Treasury, was asked to prepare a report for establishing a U.S. Mint and coinage system. Surprisingly, rather than basing his proposal for a coinage system on a silver standard defined by the Spanish milled dollar, Hamilton proposed bimetallism, whereby the U.S. dollar would be defined separately in both silver and gold, and a value ratio of silver to gold would be fixed by law. His plan ensured, though, that U.S. quarters, half dollars and silver dollars were consistent with Spanish 2 reales coins, 4 reales coins and 8 reales coins (Spanish milled dollars). U.S. coins did later trade at par with their Spanish counterparts, as Hamilton said they would.

Hamilton determined that the value of the U.S. dollar should amount to 24.75 grains of gold and, separately, 371.25 grains of silver. Hamilton created a framework for a large and comprehensive new coinage system unlike any seen before in the world.

Hamilton’s proposal was central to the Coinage Act of 1792, but this law, also called the U.S. Mint Act of 1792, differed from Hamilton’s proposal in several ways. The differences are beside the point that the U.S. silver dollar directly stemmed from the Spanish milled dollar.

Here is a direct quote from this law: “Dollars or Units—each to be of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, four hundred and sixteen grains of standard, silver.”

Flowing Hair silver dollars were minted in 1794 and 1795. Bust silver dollars are dated from 1795 to 1803. Some U.S. silver dollars dated 1803 may have been struck in 1804. No U.S. silver dollars were minted from 1805 to 1835, but quantities of Spanish milled dollars remained in circulation.

Even in the 1840s, the number of “Spanish milled dollars” that circulated in the U.S. was far larger than the number of U.S. silver dollars then in circulation. A Spanish 4 reales coin likewise was equivalent to a U.S. half dollar, and each Spanish 2 reales coin was accepted as a quarter.

Coins of the Spanish Empire were legal tender in the United States until 1857, though continued to circulate in the Western United States until the 1870s. A payment of a “silver dollar” for something in the United States during the 1830s and early 1840s was more likely to have been a Spanish milled dollar than a U.S. silver dollar.

Greg Reynolds (insightful10@gmail.com) is an independent rare coin consultant who has written more than 780 articles, which have appeared in nine different coin publications, and many private reports for clients. Greg has carefully examined a substantial percentage of the choice and rare U.S. coins in existence and a large number of condition rarities, plus thousands of vintage British, Western European and Latin American coins.